How I Cut Grad School Costs Without Sacrificing Quality

Paying for grad school felt overwhelming—tuition, fees, living costs piling up fast. I almost gave up, but then I started digging into smarter ways to manage expenses. What I found wasn’t magic, just practical strategies that actually work. From rethinking funding sources to optimizing daily spending, I saved thousands without cutting corners on education quality. If you're stressed about graduate costs, this is for you. The journey wasn’t easy, but it was entirely possible with careful planning, disciplined habits, and a clear understanding of where every dollar goes. This is not a story of extreme frugality or unrealistic sacrifices. It’s about making thoughtful, informed choices that protect your financial future while still allowing you to thrive academically and personally. You don’t have to drown in debt to earn a valuable degree.

The Rising Pressure of Graduate Education Costs

Graduate education is often framed as a pathway to professional advancement, opening doors to leadership roles, higher salaries, and specialized expertise. Yet behind this promise lies a growing financial reality that many prospective students overlook: the steep and steadily rising cost of advanced degrees. According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the average annual cost of graduate school in the United States ranges from $15,000 to over $40,000 depending on the institution type, program, and location. These figures cover tuition alone and do not include essential living expenses such as housing, transportation, groceries, health insurance, and academic materials. For many, especially those relocating or leaving full-time employment to attend school, the total financial burden can exceed $60,000 over two years.

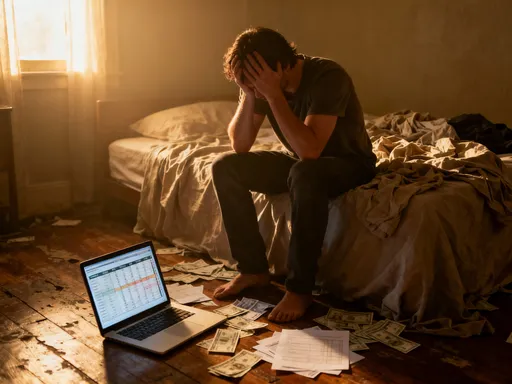

What makes this burden particularly challenging is the gap between perception and reality. Many students enter graduate programs believing they can manage costs through part-time work or modest borrowing. However, the combination of rigorous academic demands and limited time often makes consistent income generation difficult. At the same time, the temptation to maintain pre-graduation lifestyles—such as dining out regularly, leasing new cars, or living in high-rent neighborhoods—can quietly inflate monthly expenses. This phenomenon, known as lifestyle inflation, undermines financial stability even when income remains unchanged. The result is a cycle of increasing reliance on student loans, which can take decades to repay and significantly delay major life milestones like homeownership, marriage, or retirement savings.

Moreover, the opportunity cost of attending graduate school is frequently underestimated. For those who leave full-time jobs to pursue their degrees, the lost income over one or two years can amount to tens of thousands of dollars. When combined with direct expenses, this creates a substantial financial hole that must be filled either through savings, borrowing, or future earnings. Recognizing these full costs—both direct and indirect—is the first step toward responsible financial planning. It shifts the mindset from simply surviving grad school to strategically managing it as a long-term investment. Without this awareness, even well-intentioned students can find themselves overwhelmed by debt and regretful of choices made in haste.

Rethinking Funding: Beyond Student Loans

Student loans are often seen as the default path to financing graduate education, but relying solely on borrowing is neither necessary nor advisable. While federal and private loans can help cover gaps, they should be treated as a last resort rather than the primary funding source. A more sustainable approach involves actively seeking out and securing forms of financial support that do not require repayment. These include fellowships, grants, research assistantships, teaching assistantships, and employer tuition reimbursement programs. Each of these options not only reduces out-of-pocket costs but also enhances the overall value of the educational experience by providing professional development, networking opportunities, and real-world skills.

Fellowships and grants are among the most desirable forms of aid because they are typically awarded based on academic merit, research potential, or specific demographic criteria and do not need to be repaid. Many universities offer institutional fellowships specifically for graduate students, while external organizations—from professional associations to nonprofit foundations—also provide competitive funding opportunities. The key to success in obtaining these awards lies in early preparation, strong application materials, and alignment with the funder’s mission. Students should begin researching available fellowships during the admissions process and continue applying throughout their programs. Even smaller awards, ranging from $1,000 to $5,000, can make a meaningful difference when combined over time.

Teaching and research assistantships are another powerful tool for reducing financial strain. These positions are usually offered by academic departments and come with stipends, tuition waivers, and sometimes health benefits. A teaching assistant might lead discussion sections, grade assignments, or support faculty in course development, while a research assistant contributes to faculty-led projects, data analysis, or scholarly publications. Both roles provide valuable experience that strengthens resumes and builds relationships with faculty mentors. In many cases, securing an assistantship can effectively eliminate tuition costs and provide a steady monthly income. Prospective students should inquire about the availability of these positions when applying to programs and highlight relevant skills—such as prior teaching experience, technical expertise, or strong writing abilities—in their applications.

Additionally, employer tuition assistance remains an underutilized resource. Some companies offer partial or full reimbursement for employees pursuing degrees related to their job functions. This benefit often comes with conditions, such as maintaining a certain GPA or committing to stay with the company for a set period after graduation, but it can significantly reduce the net cost of a degree. Employees considering graduate school should review their benefits package and discuss options with human resources. Even if full reimbursement isn’t available, a 50% or 75% contribution can translate into thousands of dollars in savings. By combining multiple sources of non-loan funding, students can dramatically reduce their reliance on debt and graduate with greater financial freedom.

Choosing the Right Program—and Location—Strategically

One of the most impactful financial decisions a prospective graduate student can make is selecting the right program and location. While prestige and rankings often dominate conversations, they should not overshadow practical considerations like cost, affordability, and long-term return on investment. Two programs in the same field—say, a Master of Public Health or an MBA—can vary wildly in price based on whether they are offered at a public or private institution, whether the student qualifies for in-state tuition, and where the school is located geographically. These differences can result in tens of thousands of dollars in savings over the course of a degree.

Public universities generally offer lower tuition rates than private institutions, especially for in-state residents. For example, a public university might charge $12,000 per year for a graduate program, while a comparable private university charges $35,000 or more. That difference amounts to over $45,000 in savings for a two-year program. Even for out-of-state students, some public institutions offer reciprocity agreements or regional discounts that can reduce costs. Additionally, many schools allow students to establish in-state residency after one year of continuous residence, which can unlock significantly lower tuition rates for the second year. Understanding these policies and planning accordingly can lead to major financial benefits.

Equally important is the cost of living associated with a given location. A program in New York City, San Francisco, or Boston may offer excellent networking opportunities and access to industry leaders, but it also comes with extremely high housing, transportation, and food costs. In contrast, similar programs in mid-sized cities or college towns often provide a more affordable lifestyle without sacrificing academic quality. For instance, rent for a one-bedroom apartment in a major metropolitan area can exceed $2,500 per month, while the same unit in a smaller city might cost less than $1,200. Over two years, that difference translates to nearly $30,000 in housing savings alone. These funds can be redirected toward debt reduction, emergency savings, or post-graduation goals.

Furthermore, location affects employment opportunities during and after the program. Some universities are situated in regions with strong local economies and high demand for skilled professionals, increasing the likelihood of securing part-time work, internships, or post-graduation jobs. Students should research job placement rates, alumni networks, and regional employment trends when evaluating programs. A slightly less prestigious school in a thriving economic area may offer better long-term career outcomes than a top-ranked program in a high-cost, low-opportunity region. By weighing all these factors—tuition, cost of living, residency rules, and job market strength—students can make informed decisions that align with both their academic aspirations and financial well-being.

Mastering the Art of Academic Budgeting

Budgeting is one of the most effective yet underappreciated tools for managing graduate school expenses. Unlike emergency cost-cutting measures, a well-structured budget provides a clear roadmap for financial sustainability throughout the program. The goal is not to live in deprivation but to make intentional choices that reflect priorities and constraints. A realistic budget accounts for all income sources—including stipends, savings, side earnings, and financial aid—and allocates funds to essential categories such as housing, utilities, groceries, transportation, insurance, and academic supplies. It also includes a line item for discretionary spending, allowing room for occasional meals out, entertainment, or personal care without guilt or overspending.

Creating a budget begins with tracking current expenses to understand spending patterns. Many students are surprised to discover how much they spend on subscription services, convenience foods, or unplanned purchases. Using budgeting apps or simple spreadsheets, individuals can categorize transactions and identify areas for adjustment. For example, switching from daily coffee shop visits to brewing at home can save $100 or more per month. Similarly, opting for a used textbook instead of a new one, or renting digital versions through library partnerships, can reduce book costs by 50% or more. These small changes, when applied consistently, compound into significant savings over time.

Housing is typically the largest expense, so optimizing this category has the greatest impact. Students can explore shared housing arrangements, university-affiliated apartments, or off-campus rentals in lower-cost neighborhoods. Some graduate students choose to live with roommates to split rent and utilities, which can reduce housing costs by 30% to 50%. Others take advantage of on-campus housing options that may include included utilities, internet, and proximity to classes, reducing transportation needs. Transportation costs can also be minimized by using public transit, biking, carpooling, or choosing a program within walking distance of affordable housing.

Food expenses are another area where strategic planning pays off. Meal prepping, buying in bulk, shopping at discount grocers, and using campus dining plans wisely can all contribute to lower grocery bills. Many universities offer food pantries or subsidized meal programs for students facing financial hardship, resources that should be used without shame. Additionally, taking full advantage of campus amenities—such as free fitness centers, printing services, and software licenses—helps avoid unnecessary external spending. The key to successful budgeting is consistency and flexibility: reviewing the budget monthly, adjusting for unexpected expenses, and celebrating progress toward financial goals.

Earning While Learning: Realistic Side Income Paths

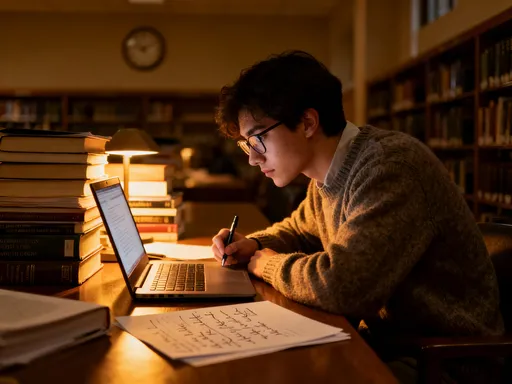

For many graduate students, income from assistantships or savings is not enough to cover all expenses, making supplemental earnings a necessity. However, balancing work with academic responsibilities requires careful planning and realistic expectations. Not all side jobs are compatible with the demands of graduate coursework, research deadlines, and teaching obligations. The most effective income-generating strategies are those that align with a student’s skills, schedule, and long-term goals. These include tutoring, freelance writing or editing, online teaching, research consulting, and part-time work on or near campus.

Tutoring is a particularly viable option, especially for students with expertise in high-demand subjects like mathematics, statistics, economics, or language instruction. Many universities operate tutoring centers that hire graduate students, offering flexible hours and competitive pay. Private tutoring, either in person or through online platforms, allows individuals to set their own rates and schedules. Similarly, freelance research or writing work—such as editing theses, formatting citations, or assisting with literature reviews—can be done remotely and fits well around academic commitments. Platforms that connect freelancers with clients in academia and publishing provide access to steady gigs without long-term contracts.

Online teaching has also become increasingly accessible, with institutions and private companies seeking subject matter experts to develop or deliver course content. Some graduate students create and sell digital study materials, such as flashcards, practice exams, or study guides, through educational marketplaces. While these ventures require upfront effort, they can generate passive income over time. Others leverage their technical skills—such as data analysis, programming, or graphic design—to offer consulting services to small businesses, nonprofits, or fellow students.

The critical factor in any side income pursuit is sustainability. Students should avoid overcommitting to work that compromises academic performance or mental health. A reasonable target might be 10 to 15 hours per week of paid work, depending on the program’s intensity. It’s also wise to communicate with advisors or program coordinators about work plans to ensure compliance with visa requirements, funding agreements, or institutional policies. When approached thoughtfully, side income not only eases financial pressure but also builds professional experience, expands networks, and enhances career readiness after graduation.

Avoiding Common Financial Traps

Even financially aware graduate students can fall into common money pitfalls that erode progress and increase stress. One of the most prevalent is overborrowing—taking out more in student loans than is strictly necessary to cover essential expenses. This often happens when students use loan disbursements to fund lifestyle upgrades, such as moving to a luxury apartment, buying new electronics, or traveling frequently. While these choices may feel justified in the moment, they result in higher debt balances and longer repayment periods. A disciplined approach involves borrowing only what is needed and depositing any excess loan funds back to the lender immediately.

Another trap is underestimating total costs. Some students focus solely on tuition and forget to account for fees, health insurance, textbooks, transportation, and emergency expenses. Failing to plan for these items can lead to last-minute borrowing or reliance on high-interest credit cards. To avoid this, students should create a comprehensive cost-of-attendance estimate before enrolling and update it annually. Building a small emergency fund—ideally one to three months of living expenses—provides a financial cushion for unexpected events like medical bills, car repairs, or sudden travel.

Credit health is another area that requires attention. Opening multiple credit cards, missing payments, or carrying high balances can damage credit scores, making it harder to secure housing, loans, or even jobs after graduation. Students should use credit responsibly—paying balances in full each month and keeping utilization below 30% of available credit. Regularly checking credit reports for errors and monitoring for fraud is also essential. Establishing good credit habits early sets the foundation for future financial success, including qualifying for favorable interest rates on mortgages or auto loans.

Finally, many students neglect to track their spending or review their financial goals regularly. Without ongoing awareness, it’s easy to drift off course. Setting up automatic savings transfers, using budgeting tools, and scheduling monthly financial check-ins can help maintain discipline. Awareness of these common traps—and proactive steps to avoid them—empowers students to stay in control of their finances and graduate with confidence.

Building a Long-Term Financial Mindset

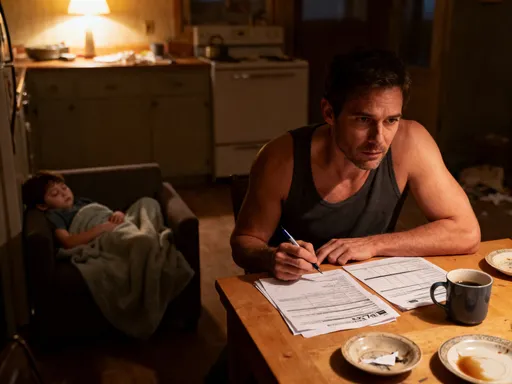

Graduate school should be viewed not merely as an expense but as a strategic investment in one’s future. How students manage money during this period has lasting implications that extend far beyond graduation. The habits formed—whether it’s living within means, prioritizing needs over wants, or consistently saving—lay the groundwork for long-term financial health. Those who graduate with minimal debt and strong financial discipline enter the workforce with greater flexibility, whether they choose to pursue further education, change careers, start a family, or buy a home. In contrast, those burdened by avoidable debt may find their options limited by monthly repayment obligations.

By optimizing costs during graduate school, students gain more than just short-term relief—they build confidence in their ability to make sound financial decisions. This mindset shift is perhaps the most valuable outcome of the entire process. It fosters resilience, reduces anxiety, and promotes a sense of agency over one’s economic future. Every dollar saved is a step toward financial independence, and every responsible choice reinforces the belief that long-term goals are achievable.

Ultimately, the goal is not to endure graduate school with the bare minimum, but to navigate it wisely—protecting both academic integrity and financial well-being. The strategies outlined here are not about cutting corners or compromising quality. They are about making informed, intentional choices that honor the value of education while respecting the reality of limited resources. With careful planning, resourcefulness, and discipline, it is entirely possible to earn a meaningful degree without sacrificing financial stability. The journey may require effort, but the rewards—personal growth, professional advancement, and lasting financial freedom—are well worth it.