How I Tamed My Car Loan and Took Control of My Finances

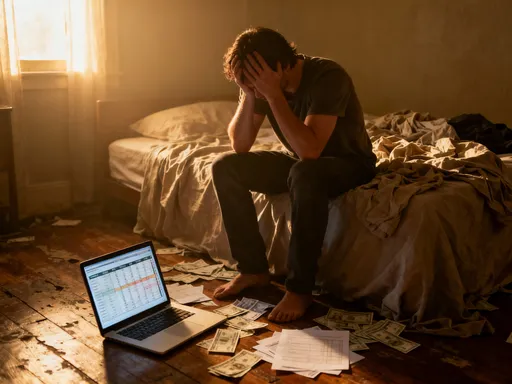

I used to dread checking my bank balance every month—especially on payday, when nearly half of my income vanished into my car payment. I wasn’t just buying a car; I was funding stress, sleepless nights, and a sinking feeling that I’d made a terrible financial decision. Sound familiar? You're not alone. Car loans are one of the most common—and often misunderstood—debt traps people fall into. But what if you could reframe your car loan from a burden into a stepping stone? This is how I did it, and how you can too. What began as a source of anxiety became a turning point in my financial journey. By understanding the mechanics of my loan, reassessing my spending habits, and making deliberate choices, I transformed a monthly obligation into a lesson in discipline, planning, and long-term thinking. The road to financial control doesn’t start with a windfall—it starts with a single decision to take ownership of your money.

The Hidden Cost of “Just a Car Payment”

A car payment might seem like a straightforward line item in your monthly budget, but its impact reaches far beyond the check you write each month. At first glance, a $400 monthly car loan appears manageable, especially if your paycheck is $3,500 after taxes. But that single expense consumes more than 11 percent of your take-home income—before rent, groceries, insurance, or savings. And unlike investments, which grow in value over time, a car begins losing value the moment you drive it off the lot. This combination of high monthly outflow and rapid depreciation creates a silent drain on your financial health.

Consider this: over a five-year loan, that $400 monthly payment adds up to $24,000—excluding interest. If the interest rate is 6 percent, the total repayment climbs to nearly $27,000 for a vehicle that may be worth only $12,000 by year five. This imbalance—owing more than the car is worth—is known as being “upside down” in your loan, and it’s a common trap. It limits your ability to trade in the vehicle, forces you to carry higher insurance premiums, and can lead to a cycle of rolling over debt into a new loan. The emotional toll is just as real. Financial strain from car payments has been linked to increased anxiety, relationship stress, and reduced spending on essentials like healthcare and education.

Moreover, carrying a large car payment affects your credit utilization and debt-to-income ratio, which lenders review when you apply for a mortgage or personal loan. A high monthly auto obligation can reduce your borrowing power when you need it most. The truth is, a car loan isn’t just about transportation—it’s a financial anchor that influences your flexibility, choices, and future opportunities. Recognizing this hidden cost is the first step toward regaining control. When you stop viewing the car payment as an isolated expense and start seeing it as part of your broader financial ecosystem, you begin to make decisions that support long-term stability rather than short-term convenience.

Why Car Loans Feel Different Than Other Debt

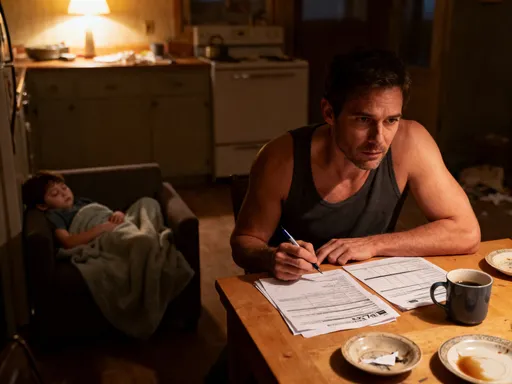

Of all the debts people carry, car loans occupy a unique emotional and practical space. Unlike credit card balances, which are often associated with guilt or impulsive spending, or student loans, which represent an investment in education, car loans are tied to daily survival. For most families, a reliable vehicle isn’t a luxury—it’s a necessity for getting to work, school, medical appointments, and grocery shopping. This practical urgency gives car loans a sense of legitimacy, even when the terms are unfavorable. Because the car feels essential, people are more willing to accept higher payments, longer terms, or larger loans than they would with other types of debt.

Dealerships and lenders understand this dynamic and often use it to their advantage. Sales tactics frequently emphasize monthly affordability over total cost. “You can drive this SUV for just $350 a month!” sounds appealing—until you realize that promise comes with a 72-month term and a $6,000 down payment you weren’t planning for. The pressure to drive off the lot with keys in hand can override careful financial judgment. Many buyers sign contracts without fully understanding the interest rate, fees, or long-term implications. The emotional high of a new car—the smell of the interior, the latest technology, the pride of ownership—can cloud rational decision-making.

Additionally, car loans are often structured in ways that make them harder to escape. Extended terms, balloon payments, and add-on products like extended warranties or credit insurance inflate the total cost while keeping monthly payments low. These features are marketed as conveniences but can trap borrowers in cycles of debt. Unlike credit card debt, which can be paid off in full at any time without penalty, car loans often come with prepayment penalties or complex payoff calculations. The sense of obligation is reinforced by the physical presence of the car itself—every time you use it, you’re reminded of the debt it represents. This psychological weight makes car loans feel more personal and harder to walk away from. Understanding these emotional and structural factors is crucial. When you recognize how urgency, emotion, and marketing influence your choices, you can pause, step back, and make decisions based on facts rather than feelings.

The Real Math Behind Loan Terms (And Why 72 Months Isn’t “Easy”)

Many people are drawn to longer loan terms because they promise lower monthly payments. A 72-month loan might reduce your payment by $100 or more compared to a 48-month term, making the car seem more affordable. But this short-term relief comes at a steep long-term cost. The longer the loan, the more interest you pay over time. For example, a $25,000 loan at 5.5 percent interest would cost about $3,600 in total interest over four years. Extend that to six years, and the total interest jumps to over $4,500—a difference of nearly $1,000. That’s money you’ll never get back, simply for stretching out the payment schedule.

Beyond the added interest, longer loans increase the risk of negative equity. Cars depreciate quickly—typically losing 20 to 30 percent of their value in the first year and up to 50 percent within three years. If you’re still paying off the car after year three, you’re likely paying for a vehicle worth significantly less than your outstanding balance. This gap becomes a problem if you need to sell or trade in the car due to a job change, family needs, or mechanical issues. You may have to come out of pocket to cover the difference, or worse, roll the remaining debt into a new loan—starting the cycle all over again.

Another hidden danger of long-term loans is the increased likelihood of mechanical problems. Most new cars come with a three- to five-year warranty. Once that expires, repair costs become the owner’s responsibility. If you’re still making payments beyond the warranty period, you could be facing $500 brake repairs or $800 transmission work while still owing thousands on the loan. This combination of debt and maintenance expenses can create a financial double bind. Lenders rarely highlight these risks during financing—they focus on the monthly number because it’s the most persuasive selling point. But as a borrower, you must look beyond the payment and consider the full timeline. A shorter loan term may require tighter budgeting, but it protects you from higher total costs, depreciation risks, and unexpected repair bills. The math is clear: lower monthly payments today often mean higher financial stress tomorrow.

Strategic Payoff: When to Accelerate and When to Hold

Paying off a car loan early is often praised as a financial win, but it’s not always the best move. The decision should depend on your broader financial picture, not just the desire to be debt-free. Accelerating your payoff makes the most sense when the interest rate on your loan is high—typically above 5 or 6 percent. In those cases, every extra payment reduces the principal faster, which means less interest accrues over time. For example, adding just $50 to your monthly payment on a $20,000, five-year loan at 6 percent can save you over $400 in interest and shorten the loan term by nearly a year. That’s a tangible benefit that improves your cash flow sooner.

However, if your car loan has a low interest rate—say, 3 percent or less—the financial advantage of early payoff diminishes. Money used to pay off low-interest debt might be better allocated elsewhere. Consider this: if you have no emergency fund, putting extra cash toward your car instead of savings leaves you vulnerable to unexpected expenses. A flat tire, medical bill, or home repair could force you to use high-interest credit cards or take out a personal loan, erasing any savings from early payoff. Financial experts often recommend building a three- to six-month emergency reserve before aggressively tackling low-interest debt.

Another opportunity cost involves investing. Historically, the stock market has returned about 7 to 10 percent annually over the long term. If your car loan interest rate is 3 percent, investing extra funds could yield a higher net return than paying off the loan early. Of course, investing carries risk, and past performance doesn’t guarantee future results. But for those with a stable income and a long time horizon, directing surplus cash toward retirement accounts or taxable investments may be more beneficial than eliminating a low-cost debt. The key is balance. Evaluate your interest rate, emergency savings, other debts, and financial goals before deciding. A strategic payoff plan isn’t about speed—it’s about alignment with your overall financial health.

Refinancing: A Second Chance or Just a Trap?

Refinancing a car loan can be a smart financial move—if done at the right time and for the right reasons. The most common benefit is securing a lower interest rate, which reduces monthly payments and total interest paid. This opportunity often arises when your credit score has improved since the original loan, or when market interest rates have dropped. For example, dropping from a 7 percent rate to 4.5 percent on a $18,000 balance could save you more than $1,200 over the remaining loan term. That kind of savings can free up cash for other priorities like debt reduction, home repairs, or family needs.

But refinancing isn’t automatically good. Some lenders market refinancing as a way to “lower your payment,” but they may extend the loan term to achieve that result. You might go from a 48-month loan to a 72-month term, lowering your monthly bill but increasing the total interest you’ll pay. This creates the illusion of savings while actually costing you more in the long run. Always calculate the total cost of the new loan, not just the monthly payment. Also, watch for fees—some lenders charge origination fees, prepayment penalties, or administrative costs that can offset the benefits of a lower rate.

Another risk is resetting the depreciation clock. If you’ve already paid down a significant portion of your loan, refinancing into a new long-term loan could put you back into negative equity. For instance, if you owe $10,000 on a car worth $12,000, you’re in a strong position. But if you refinance that $10,000 into a five-year loan, you’ll likely owe more than the car is worth for the next two years. This limits your flexibility and increases financial risk. To avoid these pitfalls, only refinance when you can secure a lower rate without extending the term, or when the extension is minimal and the savings are substantial. Use online calculators to compare scenarios and determine your break-even point—the time it takes for savings to exceed fees. Refinancing should serve your financial goals, not just provide temporary relief.

Building a Car Loan Strategy Into Your Overall Financial Plan

A car loan shouldn’t exist in isolation—it must be part of a comprehensive financial plan. Too often, people treat vehicle purchases as one-off decisions, separate from budgeting, saving, or investing. But because cars are typically the second-largest expense after housing, they deserve intentional planning. Start by setting a realistic affordability threshold. Financial advisors commonly recommend that total transportation costs—including loan, insurance, fuel, and maintenance—should not exceed 15 to 20 percent of your gross income. For someone earning $50,000 a year, that means capping transportation at $750 to $830 per month. Sticking to this guideline helps prevent overextending yourself and protects your ability to save for other goals.

Before shopping for a car, review your budget and determine how much you can comfortably allocate to a monthly payment. Then, work backward to determine the maximum loan amount you should take. Use online loan calculators to factor in interest rates, down payment, and loan term. Aim to make a down payment of at least 20 percent to reduce borrowing costs and avoid negative equity. If possible, save for the down payment instead of financing it, which keeps your loan amount lower from the start. Also, consider buying a slightly used car—just one or two years old—instead of new. These vehicles have already absorbed the steepest depreciation, allowing you to get more value for your money.

Integrate your car loan into your long-term planning by setting a payoff goal that aligns with other financial milestones. For example, if you’re saving for a home down payment in five years, aim to pay off your car before then. This improves your debt-to-income ratio and increases your borrowing power when applying for a mortgage. Automate your payments to avoid late fees and protect your credit score. And as you make progress, track your loan balance and celebrate small wins—like reaching the halfway point or paying off $5,000 in principal. These milestones reinforce positive behavior and keep you motivated. A well-structured car loan strategy doesn’t limit your life—it supports it by ensuring your transportation costs remain manageable and predictable.

From Debt to Freedom: Rethinking the Ownership Mindset

The journey from financial stress to control often begins with a shift in mindset. For years, I viewed car ownership as a symbol of success—a new car meant I was doing well. But that belief came at a high cost. I now see a car for what it truly is: a depreciating asset, a tool for mobility, and a managed expense. This change in perspective has been liberating. It allows me to make choices based on value, reliability, and long-term impact rather than image or status. I no longer feel pressured to upgrade every few years. Instead, I focus on maximizing the life of my current vehicle through regular maintenance and smart use.

This mindset opens the door to alternatives that reduce financial strain. Buying certified pre-owned vehicles, for example, offers many of the benefits of new cars—warranties, low mileage, modern features—at a fraction of the cost. Some families find that delaying upgrades by even two or three years can save thousands in depreciation and interest. Others explore different ownership models, such as leasing for business use or using car-sharing services in urban areas. The goal isn’t to eliminate car ownership but to make it intentional and sustainable.

When you finish paying off your car loan, don’t stop there. Take the payment amount you were making and redirect it into savings, investments, or debt repayment. This “ghost payment” strategy accelerates your financial progress without requiring new sacrifices. Over time, this habit builds wealth, strengthens your safety net, and gives you greater freedom. The ultimate victory isn’t just being car loan-free—it’s gaining the confidence to make informed, empowered financial decisions in all areas of life. By taming my car loan, I didn’t just save money. I gained control, clarity, and peace of mind. And that’s a ride worth taking.